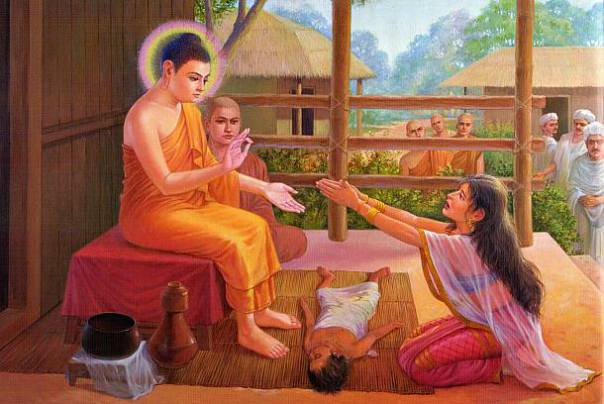

Over 2,500 years ago in India, a distraught mother whose young son had just died came to the Buddha in the hopes that he might somehow revive her child. The Buddha agreed to do so, but only if she could collect a mustard seed from a household that had not experienced death.

She went door to door in the village to see if she could find one. While every home was willing to give her a seed, none had been immune from death. After a day of fruitless searching, she finally grasped what the Buddha was trying to show her: loss is universal. The pain she felt was not unique.

Understanding this, she came to terms with her grief, and developed compassion for others who experienced similar hardship. It is said that she entered the first stage of enlightenment as a result.

Every human being, at one time or another, will experience sickness, disappointment, pain, old age, and death. Many of us experience these realities so acutely that we find ourselves completely overwhelmed, unable to proceed with our lives. The “me” before the experience is different from the “me” who emerges afterward.

How do we move on from tragedy and hardship? How can we integrate painful experiences into who we are, without letting them completely define us?

Having experienced a series of devastating losses several years ago, I began to ask myself these questions. I also began to consider how I might integrate discussions of trauma into my classes.

For a variety of reasons, many teachers don’t want to go anywhere near this topic. I certainly didn’t! How do you speak about trauma without it becoming too personal? How do you provide support to a student whose painful memories and emotions might be triggered by such a discussion?

I wrestled with these questions for several months as I contemplated how, if at all, I would broach the subject.

My search eventually led me to a surprising destination: comics.

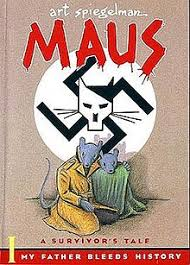

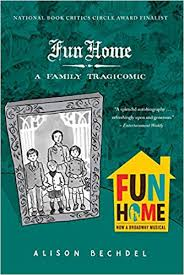

As part of my exploration into trauma, I discovered the work of Rachel Yehuda. In the fall of 2017, I invited her to Dawson to speak about her research into epigenetics, specifically her discovery that the effects of trauma can be transmitted from one generation to the next. During this talk, she mentioned Maus by Art Speigelmann, a landmark graphic novel about the Holocaust and its effects on survivors and their children.

I read Maus, and became fascinated with the potential of using visual storytelling to process trauma. I began drafting a grant proposal to explore this connection with the intention of developing pedagogical materials.

At this time, I was contacted by Mark McGuire at John Abbott College, who had attended the Yehuda talk. He proposed an idea for essentially the same type of project. We agreed to collaborate, applied for an Entente Canada-Quebec (ECQ) grant and received funding in 2018-19.

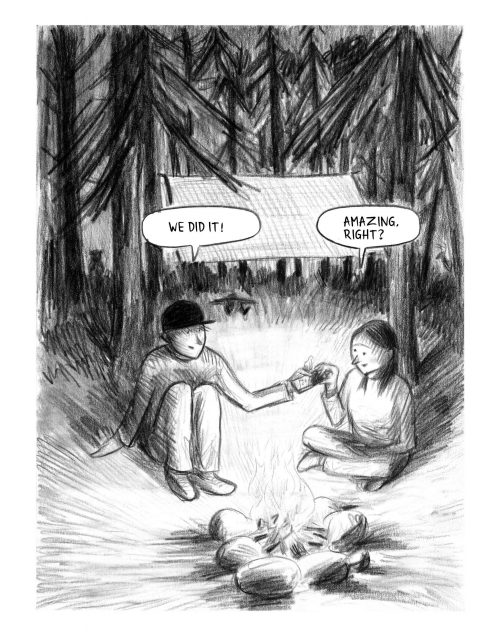

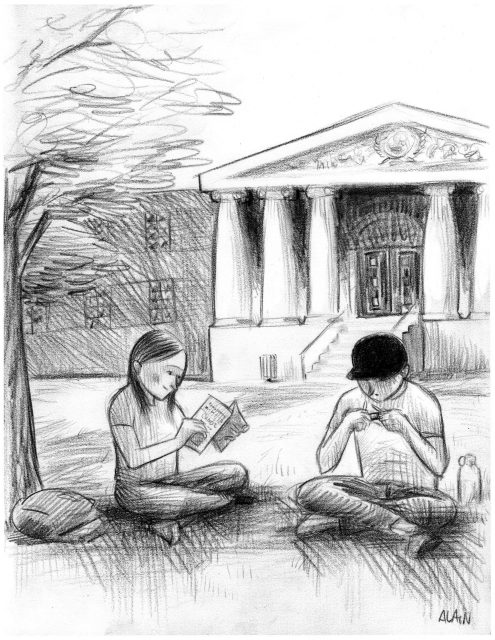

The result of this collaboration was Felix and Anya, a short graphic novel that follows two CEGEP students as they explore the impact of intergenerational trauma in their lives. For both characters, the influence of the past persists in the present, often in ways that are unconscious and unseen. Both seek to understand how their behaviour has been shaped by past generations’ response to the tragedy inherent in being alive.

The story opens a space where we can examine how to find a gift in what we might otherwise consider burdensome. For our characters, this process is catalyzed by the overwhelming power of the natural world. Along with the essential tools of courage, awareness and a supportive community, we hoped the story would encourage students to consider the pivotal role that nature can play in transforming the way they relate to themselves.

In the winter of 2019, six teachers at Dawson, John Abbott, and Nunavut Arctic College used Felix and Anya in their classrooms. Some hosted workshops with the illustrator, in which students began drawing their own stories. Giving students the tools to tell their own stories in a comic book enabled those who struggled with writing to communicate sophisticated content with simple drawings.

The teachers came from a wide range of departments, including psychology, English, and social service. This underscored a key goal of our project which was to offer material that could be used across a variety of disciplines.

Teachers were able to integrate Felix and Anya into their curriculum in their own way, tailoring the resource to their individual needs. For example, the comic was used in an abnormal psychology class as a case study for students to analyze and diagnose the conditions they thought the characters suffered from. In an English class, the story opened up a space in which to explore the relationship between narrative and identity construction. One Humanities teacher integrated the comic as part of a larger discussion about the mind-body connection, while another used it in a course on racism to explore how the legacy of a traumatic past still persists today. Finally, some Social Service teachers in Nunavut used the comic to invite discussion among their Indigenous students about their families’ experience of residential schools.

In the feedback we solicited, student responses were overwhelmingly positive. Teachers also reported that their classes were engaged with the comic, and were more excited to learn the course material than if it had been presented in a textbook.

Much of this positive response, I believe, stemmed from the use of the comic medium.

A number of artists and scholars have pointed out how comics are the medium par excellence for authors to present personal stories of trauma and recovery, in part because drawing bypasses language and can therefore suppress the ordinary inhibitions against revisiting and revealing certain overwhelming experiences. Because comics enable the visual juxtaposition of two or more time periods within a single frame, the writer-artist can situate the past in the present and foreground intrusive memories commonly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder in sophisticated ways that do not cost a fortune in special effects.

Comics also enable a kind of free association, a therapeutic method developed by Freud for psychoanalysis, where words and images from the subconscious are brought forward for reflection and critical examination. Numerous times during our production of Felix and Anya, our team would be startled by the way some images elicited personal childhood memories, which we then drew upon to guide our representation of fictional characters in the comic. We had not planned to include such images or memories, nor, in most cases, had any of us consciously thought about or discussed them in decades. The students who participated in the drawing workshops reported similar experiences.

For students, reading about trauma through the comic medium allowed them to connect with a difficult topic in a way that was more effective than simply reading about it. We repeatedly received comments such as “The comic makes a taboo subject easy to talk about” and “I was able to relate the characters’ struggles to my own life.” There was something about seeing images that brought the subject to life, while at the same time, the comic images kept the difficult experiences at a safe distance. Pain, sadness, and difficult emotions were close, but not too close.

I had experienced this myself when reading Maus. Even though I had studied the Holocaust in school, seen Schindler’s List and other films, there was something unique about presenting this tragedy in the format of a graphic novel. It allowed me to relate to the suffering in a new way that textbooks and documentaries didn’t quite capture.

Of course, broaching the topic of trauma comes with certain dangers that teachers should be aware of. One main challenge is that trauma is such a heavy subject that we risk getting bogged down in the darkness.

In developing Felix and Anya, one of our main goals was to show how trauma is not necessarily something to “overcome” or “heal,” but to integrate into our lives. The characters in the story discover that we can’t erase traumatic experiences, but we can learn to relate to them in such a way that they no longer define or imprison us. If we learn to work with them, we may even extract some benefits and understand that we owe them a great deal. As Felix and Anya discover that the pain of traumatic experiences can be transmuted into character traits that can allow us to flourish.

However, developing resilience can only happen if we have the support and the means to work through our experiences. This is why we would advise any teacher thinking of using this material in their classroom to make a list of counselling resources available, so that students can know where to turn if they feel overwhelmed.

If you are at all interested in exploring how you might incorporate visual storytelling into a discussion about trauma, I encourage you to check out the Felix and Anya website. There, you will find the comic, as well as several contextual essays that explore some of the themes that inspired its creation. There are additional resources to help you learn more about trauma from different perspectives, including psychology, biology, and spirituality. Finally, you will find suggested questions you could use to spark discussion in your class.

Studying how others have used comics to process their trauma has helped me to process my own. In the process of creating these resources for others to use, I was able to reframe the losses I had experienced and to see the ways in which my experience of tragedy has actually made me a stronger, more compassionate person.

I’d like to think that if the Buddha were around today, he might include graphic novels as one of his methods to awaken people to their inherent enlightened nature.