In the postwar period, Montreal became home to the world’s third largest community of Holocaust survivors outside of Europe. And yet their stories as well as their relationships to the city are not well known. Refugee Boulevard: Making Montreal Home After the Holocaust is a multimedia project that situates the postwar stories of survivors in the spaces they inhabited upon arriving to the city in the late 1940s.

Made possible with a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Partnership Engage Grant in 2018, Refugee Boulevard was a sixteen-month collaborative community-engaged project between researchers from Dawson College’s history department (Stacey Zembrzycki and Nancy Rebelo), the Montreal Holocaust Museum (Eszter Andor), Saint Paul University (Anna Sheftel), and nine local survivors. Zembrzycki and Sheftel have a long history of collaborative research with Holocaust survivors in the Montreal community and this project is a continuation of that relationship-building work. The result is a bilingual, one-hour, survivor-led historical audio tour as well as an accompanying booklet and website, all freely available at www.refugeeboulevard.ca. The historical audio tour enables listeners to walk in the footsteps of six child survivors who came to Montreal through the War Orphans Project in 1948 and began to rebuild their lives in the city’s Mile End and Plateau neighbourhoods. It is their voices that intimately guide listeners through the experience of starting anew.

Making Montreal a new home

Upon liberation from a variety of German labour and extermination camps in 1944 and 1945, many Holocaust survivors found themselves alone and without a home to which to return. Antisemitism remained strong and led them to seek refuge beyond Europe’s borders. But most countries heavily restricted Jewish immigration. Canada’s “none is too many” policy remained in place until the late 1940s when lobbying from the Jewish community finally made it possible for survivors to immigrate through a variety of labour schemes, family sponsorship or the War Orphans Project.

Those who came as war orphans had to be under eighteen years of age and were required to produce a dossier comprised of proof of their parents’ death, records of sound health, travel documents and release forms from the European agency caring for them. Between 1947 and 1949, the War Orphans Project enabled 764 boys and 352 girls to come to Canada, and 525 of them made Montreal their home.

As researchers, we struggled to find survivors who were still willing and well enough to be interviewed. We also had to come to terms with the gender imbalance inherent in the War Orphans Project. Nearly double the number of war orphans who came to Montreal were boys, hence we had fewer stories about this period from a girl’s perspective. Our partnership with the Montreal Holocaust Museum was central in meeting these challenges and helped us establish relationships with survivors and their families who were gracious and generous when it came time to open their homes and share their photograph collections with us.

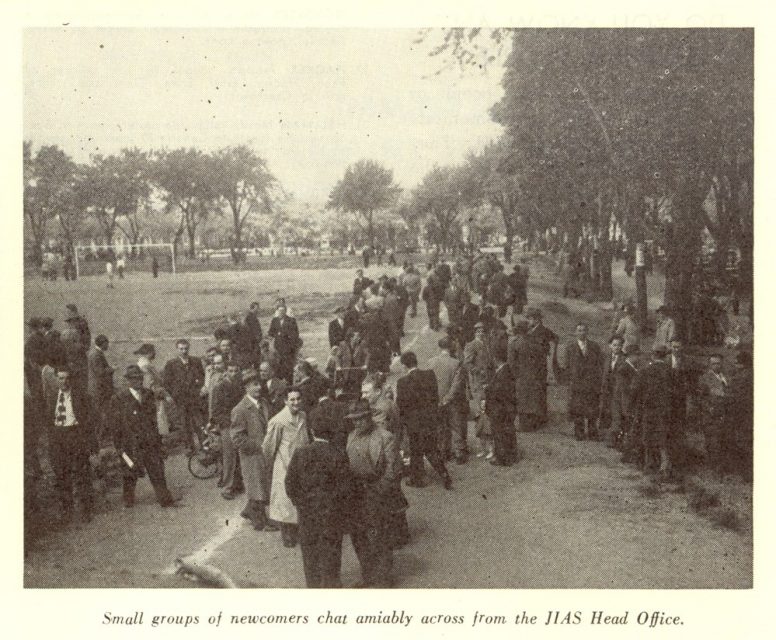

The project’s title, Refugee Boulevard, takes its name from a 1949 publication that referred to the walkway on the edge of Jeanne-Mance Park, formerly known as Fletcher’s Field, on the west side of Esplanade Avenue. It was a popular gathering place for Jewish immigrants who frequented the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society (JIAS), which operated a couple of blocks further down the street. In the years following the war, JIAS provided integration services and Fletcher’s Field served as a place for refugees to gather with friends, given the cramped and shared quarters in which they often lived in the neighbourhood. The following photograph, and powerful description, served as inspiration for us as we attempted to bring survivors’ postwar memories to life in our historical audio tour:

“… renamed ‘Refugee Boulevard’ for the large number of newcomers who on Sunday mornings fill it in such large numbers that it looks like an open-air mass meeting. The plain fact is that these people, in the words of one cop who was called by a frightened tenant, ‘are very orderly, only there are so many of them all over the street that an oncoming automobile may well injure some of them.’… In the winter, JIAS offices and corridors are jam-packed with milling humanity… As soon as the first signs of spring appear, the mass moves outside and fills the streets until such time as the wet ground of the park is dried by the sun. Then the park is occupied, and they stay in that section of the park until 1PM when the offices of JIAS close on Sundays. They stand in groups and talk in many languages. And they cover a million and one subjects…”

As well as telling new stories about the Plateau and the Mile End, the historical audio tour details the importance of open community spaces, in addition to those established by survivors themselves, such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YHMA), the Jewish Public Library (JPL), Schreter’s and the New World Club, among others. While today Holocaust survivors are well-known and respected in the Jewish community and Canadian society at large, they are often seen as one-dimensional symbols of suffering. Refugee Boulevard helps listeners connect with their complex humanity, portraying them as whole people with difficult but also mundane experiences, such as finding work and dealing with Montreal winters. The act of listening to the audio tour with one’s headphones, and walking in survivors’ postwar footsteps is both powerful and intimate. The listener hears them struggle through difficult memories and laughs at funny recollections all while they inhabit the spaces that inspired these emotions so many years ago.

Public history that is available and meaningful

Another important element of this project is that it is easily accessible to a wide audience. A key focus of ours has been to create a public history initiative that makes these stories available and meaningful for young people in high schools, CEGEPs and universities. For students, the narratives in the tour as well as on the website provide a unique opportunity to connect with Holocaust survivors from the perspective of the past but also in the current moment, given that many are the same age now as the survivors were when they began to experience the city, build new friendships and ultimately put down roots. The project has been included in various courses at the university and CEGEP level. Students who took the audio tour in Nancy Rebelo’s Social and Economic History class believed that it offered a unique perspective on the history of Montreal and the Holocaust, as well as on the experiences of newcomers. Here are some excerpts from her students’ reflections:

Stepping foot on the real locations the survivors’ experienced their lives resonated with me. I felt uncomfortable at times walking around places that survivors considered as bad souvenirs. However, hearing the voices of true survivors made me somewhat emotional. The intonation and expressions of their voices and their words really affected me. You could feel their emotions through their voices. I felt lucky to be able to hear about such personal stories. I really appreciated the tour. It opened my eyes a lot more. I think it was because of how personal we were with the survivors. The survivors would direct us as if they were with us, physically. I think this is what really made it interesting and touching.

This tour made me realize how powerful those survivors were and still are. I view them as a symbol of hope and strength. I no longer view them as only survivors but also as a sign of encouragement. I admire them even more.

I view Montreal as a gem. This city is a book filled with memories. Olivia Moreau, Dawson College

The tour reminded me of my overall experience at the March of the Living and reliving the concept of “walking through their footsteps” except this felt extremely personal because this is my home and where I grew up. The streets I cross and the institutions I enjoy.

When I arrived at the YMHA, Tommy [Thomas Strasser] recalled his first experience there … He goes on to explain that upon arriving he runs into a former friend of his who suffered alongside him in a concentration camp until liberation. The wave of emotion he displayed made my stomach turn. Crying upon seeing a man who he never thought he was going to see again … This was one of the many emotional walls I faced during this tour that I had to pass in order to keep on going.

This tour was important and I’m grateful for having had the chance to do it. This changed the way I view Holocaust survivors because I did not understand the challenges they faced when integrating into new societies, in this case Canada. The language and cultural barrier alongside coping with the incredible trauma they retained is nothing that I will ever comprehend but walking in their steps and hearing them speak about their experiences give me a glimpse into another set of challenges I had not previously considered. Furthermore, this made me begin to understand how current immigrants feel.

I have a new-found appreciation for every step I take in the city. There is a history that runs deep through the streets of the city I had never truly considered but now I can begin to understand. There are also many places that I had visited myself and had casual day to day experiences in but for these survivors, was a place to unite. Especially Fletcher’s Field which I have visited many times before without any clue about what it represents. Benjamin Elfassy, Dawson College

While some instructors have opted for the full tour experience, having students walk the streets of the Plateau and Mile End to engage with survivors’ stories in-situ, others have had students listen to the tour in class with their headphones while analysing the images in the accompanying booklet and website. Both have proven to be positive pedagogical activities.

Relationships, and a sense of community among and between groups of survivors (in this case three Hungarian male war orphans) emerge as a key way of moving forward to recreate their lives. The friendship that Ted Bolgar, Paul Herczeg, and Thomas Strasser established, and sustained over the past seventy years, is a powerful and moving element of this project that speaks to this reality. It compels listeners to understand their experiences, and also creates links immigrants and refugees who are trying to make Montreal home today.

The Refugee Boulevard audio tour brings survivors’ rich and varied stories – normally contained in museum exhibits and dusty archival collections – right into Montreal’s streets, opening up important cultural conversations around the roles that cities, neighbourhoods, ethnic organizations and everyday people play in immigrants’ resettlement experiences.

In addition to the audio tour, the Web Storytellers link on the project’s website will grow over the course of 2020 to showcase excerpts from interviews done with other survivors who arrived in Montreal through various labour schemes and family sponsorship. This too will offer students and the wider public an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of what it was like for survivors to rebuild their lives in Montreal in the postwar period. A former Dawson College Social Science student, Jasmine Anisa Cardillo, who now studies Public History at Concordia University, will be working on this portion of the project.

A project with contemporary significance

The project has contemporary significance as well. Recent legislation in Quebec, including the proposed 2013 Quebec Charter of Values and the 2018 Act to foster adherence to State religious neutrality, have set off widespread debates about the role of immigrants and “the other” in society. In drawing on survivors’ memories of the postwar period, a difficult time that was complicated by the antisemitic rhetoric of the Duplessis regime, and the vocal antisemitism of Montreal’s Francophone and Anglophone communities, Refugee Boulevard uses oral, public and local history to create powerful links between genocide, human rights violations and the current political and social crisis surrounding refugees and other minorities in our society. It is our hope that these stories – and their lessons – will not be lost on us as we move forward to try to create a just society.