Algorithmic Culture: Communication Theory + AI

INTRODUCTION

Ubiquitous in the contemporary world, AI algorithms power many of the technological tools that we use in daily life: they operate in the image processing and filtering functions of our cameras, in the newsfeed prioritization organizing our social media feeds, in search engine rankings, as well as text recommendation, cataloguing, data tracking, data analysis, and navigation systems, to name just a few of the many commonplace applications of AI.

Algorithmic Culture, the project I undertook as an AI Teaching Fellow, involved the development of a series of course modules addressing the how, when, and where of our everyday encounters with AI, the ways in which AI shapes social and cultural experiences and expressions, and the economic, political and environmental impacts of widespread digital communication.

Chief among others, the questions guiding the study concerned how culture changes when AI takes over the sorting and classifying activities heretofore the province of human beings, and what social and political functions an algorithmic culture serves. How do digital technologies affect our ways of seeing and knowing? How does our involvement in online worlds inform real-life situations? How is identity understood in the algorithmic age? How is the ‘self’ imagined and how is the social formed in the context of social networking? What are the environmental impacts of algorithmic culture? What are its biases? Can AI be used to foster a more sustainable environment and just society?

These course modules were designed to be integrated into a Communication Theory course, set to launch in the Fall of 2021. The materials presented here map the first two sections of a three-part course, and provide a description for the third. A work-in-progress, the current portfolio includes summaries of the topics to be discussed, as well as related reading/media materials for both students and teachers, and outlines for in-class exercises and assignments. The media presentations for individual lectures will be introduced as the course unfolds, added to the blog prepared for the class: https://communicationtheoryai.wordpress.com/

Part theoretical, part practical, Communication Theory (530-315) introduces students to the study of communication practices through a review of major communication theories and the conception, development and execution of a collaborative, media-based research-creation project. As defined, the course addresses the impact of AI on contemporary life as one of a number of other concerns related to changing models of communication, but the AI content will be expanded substantially for the Fall 2021 iteration.

Communication Theory (+AI) is organized as three integrated modules, each of which will introduce the student to major communication theories as they relate to algorithmic culture. The learning activities will involve readings/viewings, discussion, low-stakes writing exercises (reading responses, journal reflections, media analyses, etc.), and a series of assignments and research activities, scaffolded to culminate at the term’s end with the presentation of a collaborative media-based research-creation work. Each module will conclude with an activity (debate, discussion, presentation) that will allow students to engage the terminology and insight they’ve gained from the material reviewed.

- COMMUNICATION THEORY DESCRIPTION

- RESEARCH CREATION PROJECT DESCRIPTION

- RESEARCH CREATION PROJECT TOPICS

MODULE I: ALGORITHMIC CULTURE\

The introductory section of the course looks at the landscape of digital communications with a view to understand how new digital tools shape contemporary cultural life. We’ll start by familiarizing ourselves with the terminology and concepts defining the digital age: cloud computing, big data analytics, the Internet of Things (IoT), AI and algorithms, and discuss the role the digital plays in contemporary cultural expression. We’ll also assess whether or not and how these technologies and processes advance or restrict cultural exchange and social participation.

To discern how culture might be understood, produced and experienced differently in the computational age, we will explore changes in our understanding of culture over time.

Additionally, we will review thinking about popular culture in political and economic terms – the different inflections of “popular” or “mass culture” and “the culture industry” – and examine discourses on the political function of the popular. Does algorithmic culture require a rethinking of previous models of cultural participation that understood popular culture as a field for political exchange?

The concluding activity will involve a debate/discussion about ‘the smartness mandate’ – focusing, in particular, on smart cities, smart homes, and smart phones. Students will be asked to consider the advantages and disadvantages of smart technologies weighing claims of efficiency and security against concerns for social welfare, equality, justice and privacy.

PART IV: DIGITAL/ALGORITHMIC CULTURE AND ITS INDUSTRIES

CONCLUDING ACTIVITY: THE SMARTESS MANDATE: A DEBATE

COMMUNICATION THEORIES:

Cultural Studies: E.M. Griffin “Cultural Studies of Stuart Hall,” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012 (pages 344 – 354)

The Culture Industry and the Frankfurt School: Nato Thompson “Cultural Studies Makes a World,” Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the Age of Cultural Production, Melville House, 2015 (pages 3 – 21)

PART I: THE DIGITAL AGE?

Digital Devices include computer or micro-controllers. The Cloud stores and processes information in data centres. Big Data Analytics provides tools to analyze and make use of accumulated data. The Internet of Things (IoT) connects sensor-equipped devices to electronic communication networks. AI is a software capable of recognizing patterns. Algorithms are rules to be followed in problem solving operations, especially by a computer.

In his book The Next Internet, Communications Professor Vincent Mosco argues that the first three components of contemporary communication “comprise an increasingly integrated system that is accelerating the decline of a democratic, decentralized, and open-source Internet.” As he suggests, although it “can be a tool to expand democracy, empower people, provide for more of life’s necessities and advance social equality… it is now primarily used to enlarge the commodification and militarization of the world.”

Discussion Prompt: The accompanying presentation will sketch the different ways in which the internet has been said to advance and limit social equality. Students will be asked to inventory the concrete ways in which they participate in ‘the next internet’ and discuss whether it best serves their purposes, those of other agents, or if it has equal advantages for the Internet explorer and the data collector.

- Vincent Mosco, “The Next Internet” (1-14)

- Vincent Mosco, The Next Internet: The Cloud, Big Data, and the Internet of Things

PART II: WHAT IS AN ALGORITHM?

al·go·rithm. /ˈalɡəˌriT͟Həm/

noun

- a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations, especially by a computer. “a basic algorithm fordivision”.

Oxford Online

In the case of [the word] algorithm, the technical specialists, the social scientists, and the broader public are using the word in different ways. For software engineers, algorithms are often quite simple things; for the broader public they are seen as something unattainably complex. For social scientists, algorithm lures us away from the technical meaning, offering an inscrutable artifact that nevertheless has some elusive and explanatory power.

To chase the etymology of the word is to chase a ghost. It is often said that the term algorithm was coined to honor the contributions of ninth- century Persian mathematician Mu hammad ibn Mūsā al- Khwārizmī, noted for having developed the fundamental techniques of algebra. It is probably more accurate to say that it developed from or with the word algorism, a formal term for the Hindu- Arabic decimal number system, which was some-times spelled algorithm, and which itself is said to derive from a French bastardization of a Latin bastardization of al- Khwārizmī’s name, Algoritmi.

Tarelton Gillespie, “Algorithm” (18)

- Tarleton Gillespie, “Algorithm” (4 – 16)

- Farhad Manjoo and Nadieh Bremer “I Visited 47 Sites. Hundreds of Trackers Followed Me”

Discussion Prompt: The accompanying presentation will explore the Manjoo and Bremer visualization to understand how algorithms are used to track online activity. The follow-up discussion will consider how students use and understand the term algorithm. Are algorithms unattainably complex? Inscrutable artifacts? How does each student’s interpretation inform their understanding of algorithmic power?

PART III: WHAT IS CULTURE?

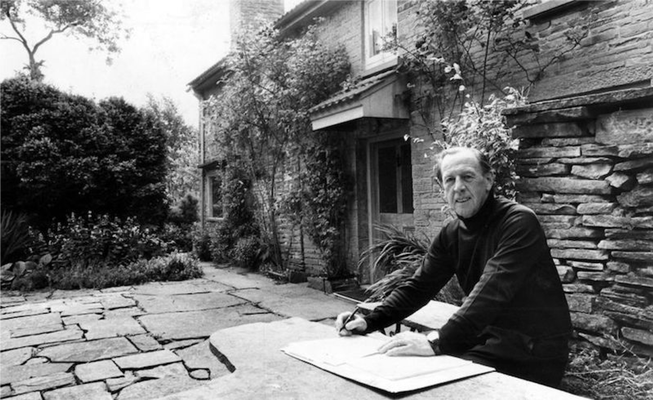

This part of the module will introduce students to the field of cultural studies. Focusing on the contributions of Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams, we’ll discuss the difference between a ‘media studies’ and a ‘cultural studies’ approach to communications, and assess the ways in which culture and its productions have been understood over time.

Stuart Hall (1932 – 2014) was a Jamaican-born, British, Marxist cultural theorist who, along with Richard Hogarth and Raymond Williams, was one of the founding figures of the school of thought that is now known as British Cultural Studies or The Birmingham School of Cultural Studies. For Hall, culture was not something to simply appreciate or study, but a “critical site of social action and intervention, where power relations are both established and potentially unsettled” (Wiki-Stuart Hall).

Hall’s contributions to Communications studies are myriad, but of particular interest to our study of culture is his understanding of the importance of the popular as a site of political engagement. He ends his influential essay “Notes on the Deconstruction of the Popular” explaining his interest in the subject of ‘the popular’:

…popular culture is one of the sites where [the] struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is also the stake to be won or lost in that struggle. It is the arena of consent and resistance. It is partly where hegemony arises, and where it is secured. It is not a sphere where socialism, a socialist culture – already fully formed – might be simply ‘expressed’. But it is one of the places where socialism might be constituted. That is why ‘popular culture’ matters. Otherwise, to tell you the truth, I don’t give a damn about it.

Discussion Prompt: The lecture/presentation will elaborate Hall’s understanding of the hegemonic processes that media uses to “manufacture consent.” Excerpts from Achbar and Wintonick’s 1992 film will be used as illustration. Our discussion will consider Hall’s argument that ‘media hegemony is not a conscious plot, nor overtly coercive, and neither are its effects total’, to consider if and how media might be used to manufacture dissent.

- E.M. Griffin “Cultural Studies of Stuart Hall” (344 – 354)

- Excerpts from Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick, Directors, 1992. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EuwmWnphqII

Raymond Williams (1921-1988) was a Welsh, Marxist theorist who wrote about politics and the media and spent the major part of his academic career trying to understand the historical factors and political functions of culture. He defined culture as the values, expressions and patterns of thoughts of members of a collective, as they are historically determined, shaped by the dominant economic and industrial modes of a given period.

Williams’ approach to studying culture involved exploring shifts in the way in which the concept itself was understood. In Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (1976) Williams chose 100 words related to cultural and social practices and phenomena, including the words culture and society, and traced transformations in their meaning over time. Some other entries in his keyword compendium include: art, management, nature, underprivileged, industry, liberal, violence. Williams’ premise was that the value placed on a concept is formed through use and application and in relationship to other ideas, words and expressions, and that terms and concepts change as new uses and applications arise; uses and applications driven by historical and political factors. Although he did not live long enough to discuss culture in the digital age his approach to cultural analysis has endured and others have taken up the mantle. In Ted Striphus’ article “Algorithmic Culture,” discussed below, the author sketches changes in the meaning of three words that are central to discussions of digital culture: information, crowd and algorithm.

Discussion Prompt: The accompanying lecture/presentation will review the principles of the ‘cultural studies’ approach discussed by Hall, with reference to Williams’ Keywords methodology, with the latter explained via the ‘keyword’ choices that Ted Stiphus makes in his explanation of ‘algorithmic culture’. In groups, students will be tasked with choosing and explaining, three words that they associate with algorithmic culture?

PART IV: DIGITAL/ALGORITHMIC CULTURE AND ITS INDUSTRIES?

In this part of the course, we’ll look more closely at cultural production in the digital/algorithmic age and examine the concept of industrial culture, querying if arguments made by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer about ‘the cultural industries’ hold true today.

DIGITAL CULTURE

Orit Halpern, a sociologist and historian of science and technology explains digital culture from anthropological and biological perspectives. From an anthropological perspective, culture “is an ontology or something that characterizes a group of people.” From the biological point of view, culture is “the medium upon which bacteria or other organisms grow.” Halpern argues for an understanding of digital culture from a biological standpoint as a “growth medium for the generation of particular forms of life…[one which is also] biologically and historically mediated.” What will grow and how it will grow is contextual.

What is digital culture? What are the potential and dangers of digital culture? What lies beyond digital cultures? What are the technological conditions of digital culture?

ALGORITHMIC CULTURE

Over the last 30 years or so, human beings have been delegating the work of culture – the sorting, classifying and hierarchizing of people, places, objects and ideas –increasingly to computational processes. Such a shift significantly alters how the category culture has long been practiced, experienced and understood…

Ted Stiphus “Algorithmic Culture”

In his discussion of “Algorithmic Culture,” Ted Stiphus considers the defining role that information technologies have played in refashioning cultural production. Expanding on Halpern’s and Williams’ definitions, he suggests that “culture is fast becoming – in domains ranging from retail to rental, search to social networking, and well beyond – the positive remainder resulting from specific information processing tasks, especially as they relate to the informatics of crowds. And in this sense, algorithms have significantly taken on what, at least since [Matthew] Arnold, has been one of culture’s chief responsibilities, namely, the task of ‘reassembling the social’, as Bruno Latour (2005) puts it – here “using an array of analytical tools to discover statistical correlations within sprawling corpuses of data, correlations that would appear to unite otherwise disparate and dispersed aggregates of people” (406).

Discussion: What does Stiphus mean when he says that culture has become the “positive remainder” of “information processing tasks” specifically “as they relate to the informatics of crowds”? What does it mean to say that algorithms have taken on “one of culture’s chief responsibilities…reassembling the social”?

THE CULTURE INDUSTRY

In 1947, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, members of the Frankfurt School of Social and Cultural Research, coined the term ‘the culture industry’ to distinguish the idea of a mass manufactured culture from a culture that defines the values and interests of the people, and to draw our attention to the ways in which culture has become commodified in the industrial age. Concerns were raised about the standardization of mass-produced cultural products, their lack of originality, innovation, higher purpose, and the utilitarian function of the mass-produced cultural work. Key to the success of mass culture was the use of mass media to seduce consumers into believing that their happiness and creativity could be satisfied with the consumption of the latest, most popular thing.

The term culture industry (German: Kulturindustrie) was coined by the critical theorists Theodor Adorno (1903–1969) and Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), and was presented as critical vocabulary in the chapter “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”, of the book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), wherein they proposed that popular culture is akin to a factory producing standardized cultural goods—films, radio programmes, magazines, etc.—that are used to manipulate mass society into passivity.[1] Consumption of the easy pleasures of popular culture, made available by the mass communications media, renders people docile and content, no matter how difficult their economic circumstances.[1] The inherent danger of the culture industry is the cultivation of false psychological needs that can only be met and satisfied by the products of capitalism; thus Adorno and Horkheimer especially perceived mass-produced culture as dangerous to the more technically and intellectually difficult high arts. In contrast, true psychological needs are freedom, creativity, and genuine happiness, which refer to an earlier demarcation of human needs, established by Herbert Marcuse.[2]

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_industry

Writing about cultural production in the digital age, Nato Thompson calls Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique “both prophetic and reactionary.” Prophetic because “Adorno and Horkheimer realized…that this new form of cultural capitalism was becoming entangled with the bourgeois ideals of individualism and taste,” and so understood that “[o]nce people accepted a cultural world produced by capital…it would be very difficult to get them to react against it” (9-10). Their critique has been perceived as reactionary because of their wholesale dismissal of the value of mass-produced culture: they didn’t seem to appreciate the discrete ways in which culture is consumed, nor understand as Stuart Hall did, that its effects are not total. Certainly, Adorno and Horkheimer could not anticipate the extent to which cultural consumption would change in the digital age: the era of Web 2.0, ‘prosumption’, sampling, hacking and commenting. Indeed, consumption has morphed into a different format for engagement – more participatory than passive. Our discussion of the ‘algorithmic cultural industry’ will look at the ways in which capital succeeds and fails to cultivate and satisfy consumer needs in the algorithmic age.

Exercise: The Algorithmic Playlist: Read the following PDF of Omar Kholeif’s ‘Algorithmic Playlists’ with a view to make some of your own: Which Youtube videos do you re-watch? Which Netflix shows are recommended to you? What books does Amazon want you to buy? Music on Spotify? Facebook or Instagram friend suggestions? Does it matter that they have been recommended to you? Do they have meaning for you otherwise?

- Nato Nato Thompson “Cultural Studies Makes a World” (pages 3 – 21)Studies Makes a World

- Geoff Cox, Joasia Krysa & Anya Lewin ed. “Introduction – ‘The (Digital) Culture Industry’.

- Omar Kholeif, “Algorithmic Playlist 1 – 3” (183 – 197)

CONCLUDING EXERCISE: THE SMARTNESS MANDATE

A debate considering the problems and possibilities of smart technologies: smart phones, smart homes and smart cities.

MODULE II: ALGORITHMIC SOCIALITY

This course module looks at the social implications of algorithmic culture. Divided in six parts, the first will view the Netflix film The Social Dilemma and consider its critical response, so to evaluate how the dilemmas of social media are articulated in social discourse and to introduce students to the algorithmic processes at work in social media. Parts two and three will consider what it means to be social on social media, and how social media defines the collective. Taking Facebook as a case study we’ll evaluate how social connections are engineered by the protocols of participation. In part four we will look at how data analytics identify the internet surfer and discuss how these identifications are understood and monetized. In part five we’ll examine the reach of the networked society and the digital divide, with a view to understand who participates in networked communication and who is left by the wayside. The final, concluding section of this module will serve as a bridge between this module and the next, with an activity that examines the rise in technological surveillance practices world-wide. Students will be presented with a visualization of international surveillance sites – an interactive map compiling data on types of surveillance and source – and asked to conduct supplementary research to try to understand how this surveillance has been understood, received and/or resisted by the subjects surveilled.

PART I: THE SOCIAL DILEMMA + MEDIA ECOLOGY

PART IV: ALGORITHMIC COMMUNITY – YOUTUBE AND SYMBOLIC INTERACTION

PART V: THE NETWORKED SOCIETY AND THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

CONCLUDING ACTIVITY: SURVEILLANCE SURVEY

COMMUNICATION THEORIES:

Symbolic Interactionism: E.M. Griffin, “Symbolic Interactionism of George Herbert Mead,” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012 (pages 54 – 66)

Media Ecology: E.M. Griffin,”Media Ecology of Marshall McLuhan.” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012 (pages 321 – 331)

Networked Society: Robert Van Krieken, “Manuel Castells + the Networked Society” April 12, 2016

PART I: THE SOCIAL DILEMMA + MEDIA ECOLOGY

Video: The Social Dilemma Preview

“We tweet, we like, and we share— but what are the consequences of our growing dependence on social media? As digital platforms increasingly become a lifeline to stay connected, Silicon Valley insiders reveal how social media is reprogramming civilization by exposing what’s hiding on the other side of your screen.”

The documentary film “The Social Dilemma” takes a unique approach addressing the social, psychological and political dynamics of social media, blending a dramatic, fictional narrative with more familiar documentary conventions: a story about a family crisis spawned by an ‘addiction’ to social media is interspersed with expert opinions by software engineers who have designed the social media platforms and processes that lie at the heart of the family crisis. The film has received a lot of critical attention – some good, some bad. Some critics agree with the filmmaker’s position on the dilemma facing social media users:

Technology’s promise to keep us connected has given rise to a host of unintended consequences that are catching up with us. Persuasive design techniques like push notifications and the endless scroll of your newsfeed have created a feedback loop that keeps us glued to our devices. Social media advertising gives anyone the opportunity to reach huge numbers of people with phenomenal ease, giving bad actors the tools to sow unrest and fuel political divisions. Algorithms promote content that sparks outrage, hate, and amplifies biases within the data that we feed them.

https://www.thesocialdilemma.com/the-dilemma/

Others argue that the filmmakers do not understand how technology works:

For all of its values, and all of its flaws, the film’s diagnosis of social media is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of technology. Its recommended path to recovery, as a result, leads to a dead-end. Until we think of technology not as a tool but as a set of relations, we will never truly grasp the problems with which The Social Dilemma is concerned…

Niall Docherty

Responding to comments made by one of the film’s stars on The Joe Rogan show, Eric Scheske suggested that while the filmmaker’s concerns about the ways in which the film present the social media may echo themes in the writing of Communications scholars Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman, neither McLuhan or Postman could have imagined how entangled we have become with our technologies.

The basic truth applied by The Social Dilemma is vintage McLuhan/Postman: The medium is the message, which means, “The content conveyed by a medium (TV, radio, newspaper) doesn’t matter. The medium and its effects on us is what matters. Media affect us, regardless of their content. To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The mere carrying of a hammer affects how a person thinks, even if he doesn’t notice it.”

Likewise, the Internet affects us, regardless of what we’re using it for. And it affects us in ways we don’t notice or appreciate. If we think we’re floating higher than everyone else because we don’t use the Internet to troll or view porn, we’re just kidding ourselves. We ’re being affected in the same way as the porning idiots.

All that is vintage McLuhan/Postman. Harris is right to give them credit.

But there’s a lot more to The Social Dilemma.

McLuhan didn’t see this coming or if he did, he thought it might, at a certain level, be a good thing.

At one point, Harris mentions that it’s almost like the algorithms are accessing our central nervous system. He obviously doesn’t consider that a good thing.

McLuhan, however, praised electronic technology because it had “outered the central nervous system itself” and had the potential of making us whole again. At other points, McLuhan expressed grave concerns, but for the most part, he was optimistic about our electronic future.

Eric Scheske, Is the Netflix Documentary a Paean to Marshall McLuhan?

More, as Scheske points out, although McLuhan and Postman may both subscribe to a ‘media ecology’ model of communication – where media act as mediums promoting the growth of human culture, and function as extensions of the human senses – they differ on one key point: McLuhan “praised electronic technology because it had ‘outered the central nervous system itself; and had the potential of making us whole again,” Postman was more circumspect. Focusing on television, he argued that “TV dumbs us down because it doesn’t engage us…the way print does by exercising our faculties of focus and thought, of stopping and re-reading, of thinking about what we’ve read. ” Where “social media bring back engagement and participation, but it’s not voluntary and, therefore, the participation is illusory. We click and think we choose; we read and think we chose to read.”

Discussion Prompts: Our conversation will begin discussing the difference between thinking about social media as a tool, versus thinking about it as a relation; and then explore the concept of ‘media ecology’ by summing McLuhan’s and Postman’s positions on electronic technology. Discussion will consider how these scholars would understand and respond to the impact of social media and new, smart communication technologies on the human sensorium.

- M. Griffin, “Media Ecology of Marshall McLuhan.” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012 (pages 321 – 331)

- Niall Docherty, “More than tools: who is responsible for the social dilemma?”

- Eric Scheske, “Is the Netflix Documentary a Paean to Marshall McLuhan?”

- Richard Seymour, “No, Social Media Isn’t Destroying Civilization,”

PART II: PROGRAMMED SOCIALITY

Concerned with the impact of algorithmic culture on social life, we’ll discuss how identity and subjectivity might be conceived and produced through our encounters with algorithms, how the collective is imagined and the social assembled through networked exchange.

A term coined by Communication and IT Professor Taina Bucher, “programmed sociality” refers to the manner through which friendships are programmatically organized and shaped by social networks. Facebook offers the perfect illustration of programmed sociality. The platform simulates and reconfigures existing notions of friendship, orchestrating the kinds and qualities of connections made to boost traffic on the site. This is friendship with benefits, but for whom?

We will explore how Facebook works to orchestrate friendship and community, how friendship is understood in social networking terms, and how the social takes form in and through social media.

Ben Grosser on the Facebook Demetricator: “The Facebook interface is filled with numbers. These numbers, or metrics, measure and present our social value and activity, enumerating friends, likes, comments, and more. Facebook Demetricator allows you to hide these metrics. No longer is the focus on how many friends you have or on how much they like your status, but on who they are and what they said. Friend counts disappear.”

Journal Exercise: Use Grosser’s Facebook Demetricator for one week; take note of how many times you check metrics and in which circumstances. Reflect on the quantitative versus qualitative value you place on your social exchange

- Taina Bucher, “Networking, or What the Social Means in Social Media” (1 and 2)

- Ben Gosser, Facebook Demetricator: A web browser that hides all the metrics of Facebook

PART III: I AM DATA

In the digital age, in addition to how we usually self-identify – naming and presenting ourselves as we want to be known and seen – our identities are algorithmically produced and mostly beyond our control or benefit. Every time we initiate a Google search or log onto a social network, streaming service or commercial website, streams of data are generated and collected, including search terms, the locations of devices, time stamps, operating systems, the applications we use and how and when we use them. Then, data collected from these online stops, shops and clicks are measured against previous search histories – ours and others accessing the same site and those others’ others’ data – to determine degrees of our correspondence to ‘measurable types’: ‘man,’ ‘woman,’ ‘queer,’ ‘straight,’ ‘old,’ ‘young,’ ‘white,’ ‘Black’ and so on. Then the advertisers (or governments) arrive to do their work. More, these identities are not stable. Each subsequent search situates our data in relation to myriad others and their others. And so it goes. As digital scholar John Cheney-Lippold suggests, “we are now ourselves, plus layers upon additional layers of… algorithmic identities” (5)

Cheney-Lippold also argues that the dynamics of identity construction in the digital age finds a degree of commonality with the thinking of Judith Butler on the subject of gender performativity, where the stability of gender identity is called into question, but without the self-determination that she imagined for the actual performing subject (25).

DISCUSSION PROMPT: The presentation will make use of James Bridle’s Citizenship Ex project to explain the concept of the ‘measurable type’, with subsequent discussion querying how algorithmic identities intersect with real lives and how exactly the categories of sex, gender, race and class matter in the algorithmic age.

- Lidia Pereira, “Soft Biopolitics (Measurable Type)” Object Oriented Subject, September 2017

- James Bridle CITIZENSHIP EX; About CITIZENSHIP EX

PART IV: ALGORITHMIC COMMUNITY – YOUTUBE AND SYMBOLIC INTERACTION

The other side of the ‘social dilemma’ is the role played by social media in building community – shaping the language and discourse through which we find common interests and define ourselves in relation to the group. This part of the course explores the ways in which social platforms are used to shape social discourse and introduces the student to the theory of ‘symbolic interaction’ developed by philosopher George Herbert Mead in the philosophy department at the University of Chicago in the 1920s.

The term ‘symbolic interaction’ describes a theory of communication that imagines human communication as a dialogue: “[t]he ongoing use of language and gestures in anticipation of how the other will react; a conversation” (Griffin, 54). Mead’s theory isolated three main features of inter-personal communication: people respond to others, both animate and non-animate beings, based on the meaning that they assign them; these meanings are shaped by social interaction, negotiated through the use of language or ‘symbolic naming’; and, these symbols are modified by an individual’s mental processing – what they think of the shared meaning, how they think that they should respond, with what symbolic interaction of their own: this is known as self-talk.

Mead’s concept of the self follows from these interactionist principles: the self is created imagining how we look to the other person. This “looking-glass self” is socially constructed. “We are not born with senses of oneself. Rather, selves arise in interaction with others. I can only experience myself in relation to others; absent interaction with others, I cannot be a self—I cannot emerge as someone” (Shepherd 24).

The premises behind Natalie Bookchin’s documentary filmmaking suggests that symbolic interactionism is alive and well in the world of social media. Her practice involves culling content from hundreds of YouTube videos and reassembling these to draw a picture of American society forged through the common interests, language and symbolic expressions of YouTube vloggers. The most striking features of her work describe the common conventions of online expression – video to video the performers adopt similar strategies of self-presentation – and illustrate the consistency of the verbal language used to address the subject at hand.

How does the work relate to algorithmic culture?

The work Bookchin has done for the last decade lies somewhere between a collaboration with and intervention into Google’s algorithms. Bookchin digs into online databases to collect videos, and by varying search terms and going deep into search results, aims to circumvent the search’s algorithmic biases. She rescues videos lost in the cacophony or buried by secret algorithms that favor more “shareable” data.

Algorithm-based recommendations offer people films, books, or knowledge based on past choices, providing what the algorithm thinks they want. Like algorithms, her montages suggest relationships between different sets of data, but unlike algorithms, which are invisible and individualized, she make her biases visible through editing and montage, and the semantic relationships she creates reveal larger social truths that go beyond the individual.

YouTube’s algorithms organize videos by popularity, tags, and titles. They can’t easily detect subtext or irony, falsehoods, or disinformation. Any politics, preferences,

ethics—or lack thereof —embedded in the algorithms are company secrets. Bookchin’s intervention aims to highlight our algorithmic condition, how we come to see and know what we do though automated algorithmic mediation, as well as to underscore the

value of embodied, situated, creative human intelligence and perspectives.

From the symposium pamphlet, Network Effects

Discussion Prompt: After discussing Mead’s theory of symbolic interactionism as illustrated in and by Bookchin’s work, we’ll consider the importance of self-talk in symbolic interaction on social media. Students will be asked to discuss their own experience of symbolic interaction in social media.

- Natalie Bookchin, Mass Ornament, 2009 / Long Story Short (2016)/ Now He’s Out in Public and Everyone Can See 2012/2017)

- Natalie Bookchin, Network Effects – Natalie Bookchin: Media Works 2008-2017, (PAGES 2-3)

- Angela Maiello. “Re-Editing the American Crisis: Natalie Bookchin’s Montaged Portraits,” DVD Portraits of America; Two Films By Natalie Bookchin, Icarus Films 2017

- M. Griffin, “Symbolic Interactionism of George Herbert Mead,” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012 (page 54 – 66)

PART VI: THE NETWORKED SOCIETY AND THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

The concept “networked society” was first introduced by Jan van Dijk in his 1991 Dutch book De Netwerkmaatschappij (The Network Society) and further developed by Manuel Castells in The Rise of the Network Society (1996): the term refers to a society that is connected by mass and telecommunication networks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Network_society).

As Castells explains, although social networks are not new, “the key factor that distinguishes the network society is that the use of ICTs helps to create and sustain far-flung networks in which new kinds of social relationships are created” (Wiki – The Networked Society). According to Castells, three processes led to the emergence of this new social structure in the late 20th century:

- the restructuring of industrial economies to accommodate an open market approach

- the freedom-oriented cultural movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, including the civil rights movement, the feminist movement and the environmental movement

- the revolution in information and communication technologies

A key aspect of the network society concept is that specific societies (whether nation states or local communities) are deeply affected by inclusion in and exclusion from the global networks that structure production, consumption, communication and power. Castells’ hypothesis is that exclusion is not just a phenomenon that will be gradually wiped out as technological change embraces everyone on the planet, as in the case that everyone has a mobile phone, for example. He argues that exclusion is a built-in, structural feature of the network society.

In part this is because networks are based on inclusion and exclusion. Networks function on the basis of incorporating people and resources that are valuable to their task and excluding other people, territories and activities that have little or no value for the performance of those tasks (Castells 2004 p. 23). Different networks have different rationales and geographies of exclusion and exclusion – for example, Silicon Valley engineers occupy very different social and territorial spaces from criminal networks.

The most fundamental divides in the network society according to Castells (2004 p. 29) are the division of labour and the poverty trap that we discussed earlier in the context of globalisation. He characterises these as the divide between ‘those who are the source of innovation and value to the network society, those who merely carry out instructions, and those who are irrelevant whether as workers (not enough education, living in marginal areas with inadequate infrastructure for participation in global production) or as consumers (too poor to be part of the global market).’

Managing Knowledge and Communication for Development – “Unit 1 Introduction to Knowledge, Communication & Development: The Networked Society“

It’s important to look at the “digital divide” in terms of the degrees and reasons for exclusion involved:

It was traditionally considered to be a question of having or not having access,[4] but with a global mobile phone penetration of over 95%, it is becoming a relative inequality between those who have more and less bandwidth[6] and more or less skills. Conceptualizations of the digital divide have been described as “who, with which characteristics, connects how to what”:

- Who is the subject that connects: individuals, organizations, enterprises, schools, hospitals, countries, etc.

- Which characteristics or attributes are distinguished to describe the divide: income, education, age, geographic location, motivation, reason not to use, etc.

- How sophisticated is the usage: mere access, retrieval, interactivity, intensive and extensive in usage, innovative contributions, etc.

- To what does the subject connect: fixed or mobile, Internet or telephony, digital TV, broadband, etc.

Wikipedia with help from Bart Pursel, “The Digital Divide” in Information, Technology, People, Penn State University, n.d.

Discussion: Castells argues that exclusion is a built-in, structural feature of the network society. Why and how is exclusion built-in? Discuss.

- The Networked Society (August 19, 2019)

- Robert Van Krieken, “Manuel Castells + the Networked Society”

- Visualizing the Global Digital Divide

- Wikipedia with help from Bart Pursel, “The Digital Divide” in Information, Technology, People, Penn State University, n.d.

CONCLUDING ACTIVITY: SURVEILLANCE SURVEY

The final activity for this section of the course will involve the class in a group research project looking at how artificial intelligence is used as a form of governmental surveillance, gathering and monitoring information on its citizens. Our survey will engage the “AI Global Surveillance Technology Index” prepared by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to explore the different digital tools used for these purposes.

SURVEILLANCE SURVEY: DESCRIPTION

MODULE III: DATA VS. IMAGE (in progress)

Module III will explore the differences between lens-based representation and data visualization; how each form has been understood and engaged. In four parts, we will: 1) survey the prehistory of dataset production, looking at the early photographic archives as a historical means of social engineering, and examine the contemporary racial and social biases of contemporary archives/datasets at work in facial recognition software; 2) explore how digital technologies have challenged the documentary value of lens-based imaging; 3) consider the role and value of nonhuman photography in the production of knowledge; 4) and evaluate whether or not and how data visualization can make historical phenomena intelligible and meaningful. The concluding activity will consider how processes of visualization have changed in the computational age.

PART I: ARCHIVES, DATASETS + THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SOCIAL

PART III: NONHUMAN PHOTOGRAPHY

CONCLUDING ACTIVITY: THE COMPUTATIONAL TURN

COMMUNICATION THEORY:

PRELIMINARY BIBLIOGRAPHY

Taina Bucher, “Networking, or What the Social Means in Social Media.” Social Media + Society April-June 2015: 1–2

Natalie Bookchin, Network Effects – Natalie Bookchin: Media Works 2008-2017

Niall Docherty, “More than tools: who is responsible for the social dilemma?.” October 2020 Social Media Collective, https://socialmediacollective.org/2020/10/05/more-than-tools-who-is-responsible-for-the-social-dilemma/

Stephen Feldstein “The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance” (September 2019). https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/09/17/global-expansion-of-ai-surveillance-pub-79847

Tarleton Gillespie, “Algorithm” in Benjamin Peters, ed. Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information, Society and Culture, Princeton University, 2016 (pages 4 – 16 of 352 pages)

E.M. Griffin “Cultural Studies of Stuart Hall,” “Symbolic Interactionism of George Herbert Mead” “Media Ecology of Marshall McLuhan,” and “Semiotics of Roland Barthes,” A First Look at Communications Theory, 8th ed. McGraw Hill, 2012

Stuart Hall, “Notes on Deconstructing ‘The Popular’,” People’s History and Socialist Theory, Raphael Samuel (ed.), London: Kegan Paul-Routledge, 1981, pp. 231-5, 237-9.

Orit Halpern, Robert Mitchell, and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan . “The Smartness Mandate: Notes toward a Critique.” Grey Room 68 (2017): 106–29.

Carolyn Kane, “Dancing Machines: An Interview with Natalie Bookchin,” Rhizome, May 27, 2009

Omar Kholeif, “Algorithmic Playlist 1 – 3” in Goodbye, World! Looking at Art in the Digital age.Sternberg Press, 2018.

Farhad Manjoo and Nadieh Bremer “I Visited 47 Sites. Hundreds of Trackers Followed Me.” By (August 23, 2019) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/23/opinion/data-internet-privacy-tracking.html

Vincent Mosco, “The Next Internet,” Becoming Digital: Toward a Post-Internet Society. Emerald Publishing, 2017

Lidia Pereira, “Soft Biopolitics (Measurable Type)” Object Oriented Subject, September 2017 https://www.objectorientedsubject.net/2017/09/soft-biopolitics/

Scheske, Eric. “Is the Netflix Documentary a Paean to Marshall McLuhan?” The Daily Eudemon, November 13, 2020. https://thedailyeudemon.com/?p=52157.

Richard Seymour, “No, Social Media Isn’t Destroying Civilization,” Jacobian, September 9, 2020 https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/09/the-social-dilemma-review-media-documentary

Ted Stiphus “Algorithmic Culture” European Journal of Cultural Studies (2015), Vol. 18 (4-5) 395–412

Nato Thompson “Cultural Studies Makes a World,” Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the Age of Cultural Production, Melville House, 2015 (pages 3 – 21 of 197 pages)

Wikipedia with help from Bart Pursel, “The Digital Divide” in Information, Technology, People, Penn State University, n.d. https://psu.pb.unizin.org/ist110/chapter/9-3-the-digital-divide/