Cassia Powell: in between you and me

in between you and me is a solo exhibition of select works by Vancouver-based emerging artist Cassia Powell.

This body of work develops themes exploring what writer Gavin Butt refers to as a ‘social activity which produces and maintains the filiations of the artistic community,’ namely – gossip. Using soft-sculptures and oil paintings, in between you and me explores intimacy, vulnerability, story-telling, and worldbuilding through painting and fibres-based installation. Approaching gossip as a form of unconventional art history, or an inescapable feature of metropolitan artistic life, and exhibiting it through a queer, quotidian, affective visual approach.

Biography

Cassia Powell (they/them) is an emerging contemporary artist and curator based in the unceded lands of Lekwungen-speaking peoples, otherwise known as Victoria, BC. Powell is a BFA Visual Arts honours graduate from the University of Victoria. Between their personal artistic practice and their curatorial focus, Powell’s work explores comfort + care as a radical act of social resistance through a combination of soft sculpture and oil painting.

They are the co-founder of the Dirty Dishes Collective, a curatorial project which aims to support emerging artists and cultural practitioners as a site of critical discourse, creative experimentation, and community engagement.

Cassia has exhibited at Open Space (Victoria), ED Video Guelph (Guelph), and has been nominated for the BMO First Art Award. Most recently, they exhibited their second solo exhibition, “Playthings”, at 100% Silk (Toronto).

Cassia Powell acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts. www.canadacouncil.ca

Featured artists:

Cassia Powell

Interview with Cassia Powell

by Olivia MacIntosh and Tristan Boisvert-Larouche

O.M.: This exhibition explores queer art history through gossip. Why was it important for you to show queer art history through gossip, especially since you could argue that gossip has negatively impacted young queer folk. (For example: rumors about a person’s sexuality).

C.P.: This is a good question, and it did come up for me quite a bit while I was developing this show, but I was kind of looking at it not so much as gossip about queer folk but gossip between queer folk. It is interesting that while I was putting the work up it was the first time that people were saying, isn’t gossip a really bad thing, why would you want to talk about it? I did some research into the subject to try to understand why it has such a bad reputation. If you look at it from a feminist perspective, gossip was something that started between women, and people often looked down upon it. This complicated relationship between women was associated with rumors and malicious intent. It was seen as being devious, but it wasn’t necessarily the case. It was often just like swapping stories and recipes or looking out for each other.

The idea is based on a book called In Between You and Me – the whole show, including the title, most obviously was heavily inspired by it. The author, Gavin Butt, talks a lot about the queer community in New York in the 50s and 60s and how they were looking to other gay artists for support; they wanted to know who to work with, who you could trust with coming out but none of this was really documented in a conventional way. They had to rely on this type of word of mouth. It was kind of a way to facilitate safety within these spaces.

You can’t really have a conversation about gossip without addressing the positive and negative aspects of gossip, and the horrible ways it has impacted the queer communities. It is a really interesting history to look at, I think there are good and bad aspects of gossip. I don’t see the show as so much of a celebration of gossip, but more like a commentary. A lot of the works in the show have this push and pull between comfortable and uncomfortable. You’ll see that in a lot of the depictions of these figures.

T.B-L.: I noticed that your earlier work was more focused on online culture, what initially drew you towards the idea of exploring a more personal idea of "gossip as a form of unconventional art history"?

C.P.: I am glad that you noticed that because it’s something that has really stayed with me. I feel like this was a departure from being online, from having grown up in the digital age. I had been working on this other exhibition as a curator with another artist-curator who works explicitly with archives. This was a way for me to break away from a subject I had become hyper-fixated on. I wanted to expand on the topic of the inner workings of relationships, complicated and gross but comforting feelings, but I wanted to apply it to another theme, which in this case was archives and gossip. So, I did have some external influences in this regard.

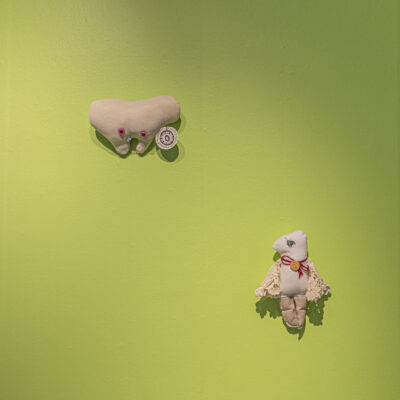

O.M.: What is the significance of playthings™-- and how do they relate to the concept of queer art history and gossip?

C.P.: Are you familiar with the Carrier Bag Theory by Ursula K. Le Guin? This is something that I was introduced to recently. Le Guin is a prominent feminist sci-fi author, but she also wrote this anthology – in an essay she talks about the carrier bag theory: people often assume that the first tools that mankind used were hammers or weapons, but she argues that it was actually a pouch worn by women to carry food, berries or even their children. It’s less exciting so it doesn’t get talked about as much. She goes on to explain that this carrier bag is also like a vessel for memory, lots of people have brought this idea into new contexts and it’s an idea that really inspired me. When I was first making these, it was for a different solo show I did a couple of years ago, I was thinking of these playthings™ as ways to hold precious memories and fragments. The materials they are made of are old sweaters from my family or pillows or blankets or handmade buttons, that were given to me. I then make them into these old, nostalgic looking toys, objects that also carry a lot of stories within them. I was someone who obsessively collected webkinz when I was younger, they each had a name and a backstory. I could tell them things that I couldn’t tell other people, it was a way for me to learn how to communicate. The playthings™ come with tags that I made that take you to a website I created that goes into the backstory for each toy with the story that it’s inspired by and about the fabric it’s made of. They are about holding memories but I recontextualized them for this show.

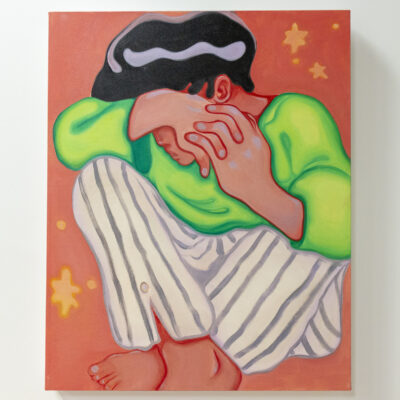

O.M.: I noticed the characters you paint resemble humans, but they also have fantastical features. Is this a purely stylistic/aesthetic choice or is there a particular reason you painted them the way you did?

C.P.: I think yes to both! It’s definitely my style, but it also has to do with the fact that when I was in my third year of university, I did a three-month residency in Northern Iceland. The place where I was doing my residency was right next to a folklore and witchcraft museum. I ended up making a lot of drawings and being inspired by the local folklore. This interest led me to look into the world of goblins and demons, and the history of the area, which is kind of a contemporary history. People there still believe in these goblins and stories. This was an old fishing town, and people would put their shoes in certain places, or would not leave their lights on past a specific time so as not to upset the spirits. I was fascinated by the omnipresent combination of fiction and non-fiction, and the fact that folklore still has

such a grip on modern society. So, all of the figures in my paintings were influenced by this and have maybe not demon-like quality but they have furrowed brows and brightly coloured skin. It has changed over the years, as I have developed my work, they kind of became these fantastical representations of grief or depression or euphoria. The colours and dramatic facial features become emblems of emotion. Also, it’s really fun to paint people like that.

O.M.: I got the sense that in certain paintings (slumber party diptych and cheated) the characters look like they are in pain or are sick. Why is that?

C.P.: I think this is similar to what I was just saying, they are supposed to be overdramatic representations of certain emotions. It is also like an extension of my own experiences, specifically in the piece Slumber Party diptych I was trying to capture the feeling of having a breakdown at a slumber party and the kind of fear, guilt, and shame that gets twisted into it. There is kind of a little bit of a narrative you put on it when you are supposed to be in this area of comfort among friends. You’re swaddled in blankets and maybe wearing your favourite pajamas, but you’re still overwhelmed with too many emotions.

T.B-L. + O.M.: Considering that installation and curating are essential parts of an exhibition, what drove the choices you made in regard to the placement of your artworks and the green colour of the walls?

C.P.: This is a really fun question. It was kind of an impromptu decision that I made before the show. The shade of green on the walls is called Gossip Green, and it’s in the same family as envy. I thought it would be interesting to fill a whole section of the space with this colour; so that it would take up your visual perception. But I didn’t want it to take up the whole room because there are some pieces in the show that carry a certain softness, a softer colour palette, and are a bit dreamier. I separated the works into day and night almost, if that makes sense. On one side of the gallery, where Comforter is (the star-shaped quilt), is the softer, more delicate side – the more comfortable side. Whereas the other side where the green takes up most of your field of vision is where the darker paintings are – with black, deep purples, or blues. There is a sort of nightmare-daydream relationship between the two. I also thought green made sense for the reading nook because this space is different from the rest of the exhibition, it needed to be its own little space – the green helped to delineate that space.

O.M.: I asked about the significance of the colour green but do any other colours hold particular significance? Personally, pink is another colour that stood out to me.

C.P.: Colour has always played a huge role in my paintings, I love using acidic colours – I think they are juicy and delicious. I was trying to use pink a lot because it made sense to me. Most of these pieces are based on personal experiences and my reality, and I was leaning towards this dramatic kind of fleshy colour. Something that is really similar to reality but not quite. I think the pink I was working with was called radiant rose or something and I kind of wanted it to feel like the colour was overpowering your retina. Like it’s loud and it needs to be looked at. But it’s also because during my early painting days I was working more with digital ephemera. I would often take my sketches and then bring them into Photoshop to colour them in using the most outlandish screen colours that you can’t really replicate

with actual paint, and then try to replicate them through painting. A lot of it is from CMYK, just super bright web-safe colours.

T.B-L.: A reading nook is a pretty unconventional addition to an art exhibition, what motivated you to include one in your exhibition?

C.P.: It’s something I have been playing around with a lot and has come into fruition over the past couple of years. I do a lot of curatorial and programming work with a collective, that I am part of, called the Dirty Dishes Collective ( https://www.dirtydishescollective.com/) We do a lot of community-based programming, creating alternative modes of bringing people together within academic spaces. Something we had been doing for a couple of years was creating a zine library as a way of showcasing other perspectives and bringing them into the academic context. Even when you have a solo show, you are never doing anything completely alone, it’s never just one person. There are always so many more thoughts and concepts and ideas that belong to other people or are shared and I think they deserve to be brought into perspective. It’s very difficult, especially in the context of this exhibition, when you’re talking about queer history in such a broad sense, to do so alone; it makes sense to bring in other voices.

For the past couple years, I have been thinking more about accessibility in art spaces and making sure that people will be able to have a better understanding of what they are encountering. If this is the first art exhibition someone has ever been to, where do they start? So having this reading nook makes things a bit more user-friendly, and also provides somewhere to sit in a comfortable chair.

T.B-L.: What is, for you, the relation between academia and art-making; how does literature which explores identity and social connections influence your creative process?

C.P.: It’s so funny because when I was going through art school I had such a staunch anti-academic approach and I was really championing more low-brow forms of art, like folk art. I was young and radical and hating on all things to do with “the man” but I have grown to appreciate some of its more nuanced aspects. There are just so many perspectives that you can’t just garner your own. It’s good to include outsourced information and allow instances of stepping into a new community. I put one Canadian arts literature magazine on display on one of the shelves. I’ve been obsessed with this magazine since I’ve had the subscription because I’m starting to notice more and more names within C Magazine that I know. These people are my peers and people who have stayed on my couch when they were in town. It’s not about me hating this massive institution anymore, it’s actually a community of like-minded people sharing similar perspectives. So, I kind of see my art practice as a community-based one. I often get my ideas from other people, from sharing studio space with other artists, and I think you just can’t really do these things alone.

T.B-L.: Many of your works contain found objects that have made their way to you through family, friends or have been thrifted. What does using something that has been part of someone's life within your artworks means to you and what is your process to decide which objects to use for any given artwork?

C.P.: That is a really good question. I don’t want to just chalk it up to intuition or subconscious decision making. A lot of the people in my life know who I am, what I do and what I like. They will often give me things that they know will speak to me in some way, shape or form.

I think the first time I took an object or material from someone else and implemented it in my work was when I was visiting my parents in the context of the sale of my childhood home. We went through a bunch of boxes of things, and I was feeling so sentimental and sad about it. They gave me a huge yellow quilt, which later became the star-shaped comforter piece. My mom had said, “Oh, I don’t know if you are going to like it, it’s falling apart a little bit, but it’s been in our family for so long. You could cut it up.” Maybe this is like a “selfish artist moment” but I was just thinking about how gorgeous the colours were and I was really drawn to the way the fabric was falling apart. I wanted to keep that aspect as it held so much history; it’s been passed down multiple generations and it was almost a challenge to use it. So, it was a combination of things visually: about how does it looks, what the extent of the story behind it is, and how can I make this work together with my paintings. The stories that they carry with them are a huge part of it, and it’s about how we interact with the world: a combination of story and intuition.

T.B-L.: Your current exhibition combines new work as well as previous work which featured in some of your past exhibitions--such as comforter or your playthings™--under the theme of gossip. How important is reusing and recontextualizing previous artwork under a new perspective to you as an artist?

C.P.: It’s very important. On a completely practical note, I did not realize how big the exhibition space was when I first applied, and I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to create 15 brand new pieces. I had in my bandwidth the ability to make about four or five. I can say as much as I want about the pieces that I make but how they are presented can completely rewrite the story behind each work and I think it’s good practice for me to kind of take a step back and try to look at how these paintings might be considered through somebody else’s eyes. Because most of these pieces are based on my personal interests—and what I’m interested in hasn’t shifted a whole lot in the past few years—it was pretty easy to bring them all together. I think it provides a rich, deep kind of expansion on each work; it brings them into these new potential histories, which I am super happy to do. It makes the work feel a little bit more valuable and allows it to exist beyond the confines of the original context.