Lan (Florence) Yee: Sharp Tools for Unripe Fruit

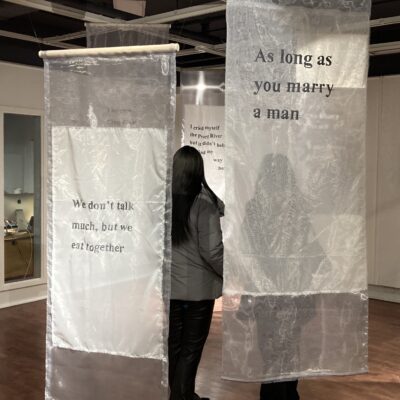

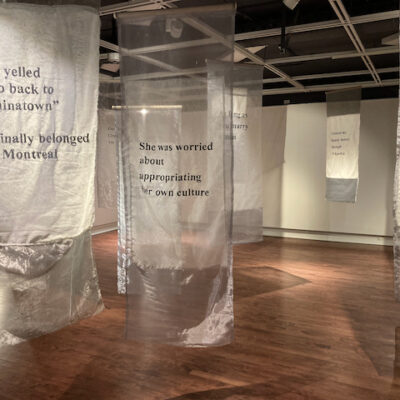

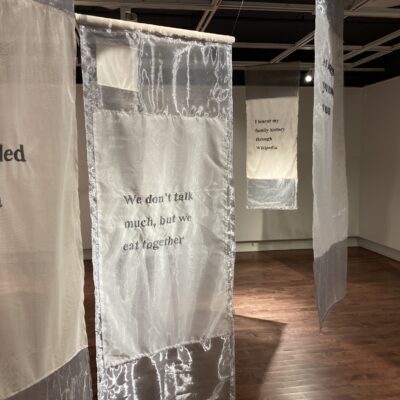

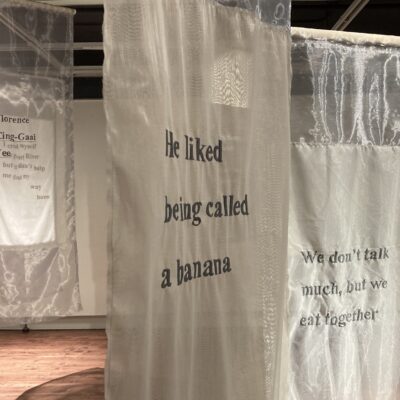

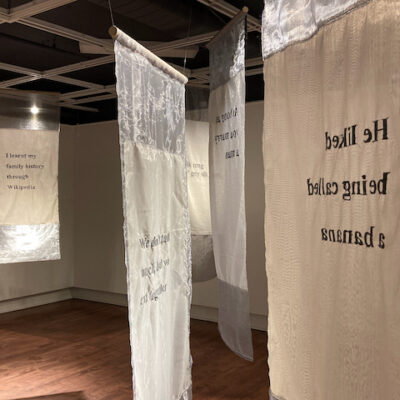

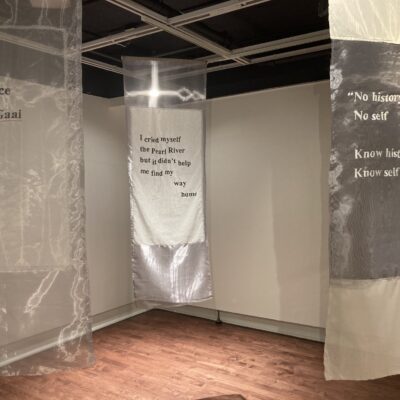

Sharp Tools for Unripe Fruit underscores the awkwardness of monumentality and its precarious taste for nostalgia. The unfinished business of commemoration takes the form of hand-embroidered text, choosing the anti-spectacular visual elements of watermarks and default fonts.

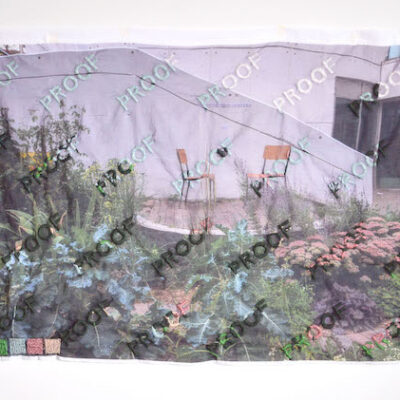

Inspired by traditional printmaking processes, the PROOF series attempts to hold the desire for archival presence with the problems of its structure. In these interrupted photographs, the various subjects are unable (or unwilling) to be claimed. Facing them, the labyrinth of Selected Hauntings engulfs the gallery’s white walls, making it complicit in its content. The pieces borrow the institutional pen of templates, academia, and forms, while displacing their functions through distrustful lived experiences. Written with a meticulous discomfort, Yee’s work bears witness to the afterthoughts of hegemonic culture: gendered expectations, racialized anxieties, relationships with bad boundaries. The exhibition outlines a recipe for a sour mix of grief and longing.

Lan (Florence) Yee is a visual artist and serial collaborator based in Tkaronto/Toronto and Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal. They collect text in underappreciated places and ferment it until it is too suspicious to ignore. Their work has been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art (2021), the Art Gallery of Ontario (2020), the Textile Museum of Canada (2020), and the Gardiner Museum (2019), and many others. Along with Arezu Salamzadeh, they co-founded the Chinatown Biennial in 2020. After graduating from Fine Arts at Dawson College, they obtained a BFA from Concordia University and an MFA from OCAD U.

Featured artists:

Lan Florence Yee

Interview with Lan Florence Yee

by Sabrina Schmidt (questions) and Victoria Petrecca-Berthelet (interviewer)

VPB: Some of the phrases in Selected Hauntings are shocking and at the same time, unfortunately, not so unimaginable. What was the process of compiling these phrases like? Are there any that you would have liked to add?

LFY: They are all things I have heard in person, that I have experienced. I use the notes app on my phone to record things or events that stick with me. I do this for myself, I don’t write these notes solely to transform them into art, I try not to look back on them. I am unsure why these words/statements matter to me or why they stick with me. However, I am deeply interested in understanding myself. Most of the time when I take notes it’s not really for my practice. It’s for me, but sometimes they end up in my work.

Selected Hauntings was the result of a five-week residency at the McLaughlin Gallery. I had a defined amount of time and I was limited to the sewing machine and iron, which were the only tools available in the gallery. I tried to make the texts as short and simple as possible. I wanted them to be taken in and processed as quickly as an image would be. I chose black and white fabrics to refute the fetishization of colourful brocades and embroidery associated with East-Asian art. I don’t want people to have preconceived expectations of my work just because of how I look.

VPB: Did you feel like you had to censor yourself?

LFY: I do censor myself in some ways but I do it out of care for myself and for others. I don’t always ask for permission when I use things said by family. I also tend to use ‘you’ and ‘I’ with the intention of making the statements more ambiguous, more open, and not gender-specific. Usually, there is no clear antagonist or protagonist, so it’s not clear who these are about.

On the subject of using text within their work, Florence has been asked if they consider themselves to be a writer or a poet but they don’t see themselves in this way. Mostly because labels are not important to them.

VPB: A series like Selected Hauntings could continue evolving over time and grow to become an even bigger collection. Can you see yourself possibly adding to them (crossing out/editing what you've already embroidered)?

LFY: I don’t usually touch work I deem finished but the idea can evolve and turn into or become part of a new project. Also, this is work I made four years ago, so I don’t relate to it as much now. Recent work features embroidery on a printed version of a carpet I once owned – so I am always interested in material and objects and our relationship with them. I continue to explore the text but not in the scroll format, and not with organza. The material I work with is a tangible manifestation of the phrase I am working with, and I am curious to see what these phrases mean outside of a haunting.

VPB: What is it about the unfinished, draft-like quality of your work that relates to nostalgia? If these images looked machine-made or mass-produced do you think that would situate the viewer too much in the present and not allow us to reflect on the past?

LFY: I am interested in the imperfect aesthetic of hand-embroidery– even with the photographic works, the texture and imperfections are visible. I choose fonts that mimic machine-made embroidery. Fonts and words are like signage, a system, a signifier. I also photograph things that resist archiving. I feel complicit with photography because of its inability to accurately or fully depict a person or a place, yet I continue to take a lot of pictures, mainly with my phone.

VPB: You’ve referred to hand-embroidering as a way of “using labor as material” and as a time-consuming practice. Is it possible that part of the reason these works are nostalgic is because of the time you have to reflect on them as you sew? Can you envision these objects being nostalgic in the future of the work you’ve put in now?

LFY: I use nostalgia to work with the abstract material of time. But, I am skeptical of nostalgia and also interested in how it operates and interested in using it to point out certain things we might take for granted, like displaced traditions.

VPB: You’re working with delicate and transparent fabrics whose edges are always going to fray. When they have to be trimmed, the panel gets smaller and the message bigger in proportion. Could this be interpreted as how over time our memories are reduced to the core as we forget the “outer” details? Was the idea of how your artworks would be subject to time something you considered beforehand?

LFY: So while in residency at the gallery, their only supply was a sewing machine and iron, which gave me the inspiration behind the material and approach I would take to my project. The organza was purchased on sale and also, I had to fit it all in my suitcase – there were a lot of arbitrary choices. For example, if I run out of a specific colour of thread, and then find out that it has been discontinued, I then have to use a different colour. This creates another imperfection. Many aspects of my work are the result of chance.

The fraying of the material over time is coincidental - it has been exhibited four times now. Fraying wasn’t necessarily part of the intention but it is part of my interest in the imperfect, ‘sloppy’ aesthetic of the series.

VPB: We’re in a time where everything needs to be done fast, and there is pressure to produce a lot in little amounts of time. Photography and embroidery are both detail-oriented and time-consuming processes. Do you feel this pressure?

LFY: I actually choose to work with hand-embroidery to slow down the artistic process. I remember that, as a student, a lot of teachers pointed out that I came up with an idea and then would execute it very quickly. So I try to slow myself down; I am still figuring out how to work more slowly. Also, as a young artist, you get used to the art school regimen of three weeks per project and then a critique. Slowing down to embroider keeps me sane and allows me to reflect on one thing for a long time.

VPB: Is all of the embroidery done by hand? Do you keep track of the amount of time you spend working on one piece? Do you ever collaborate with others on projects?

FY: Yes it’s all done by hand. A lot of people ask about the time it takes to create a piece. I don’t really keep track but I do know the amount of time it takes to complete one embroidered letter so that I can make an estimate.

I do collaborate with others, often friends. I really cherish unscheduled time with friends/studio mates. Collaborations are often born out of seeing something on the side of the road and thinking “wouldn’t it be funny if…?”

Lan then showed us a plaque they made in collaboration with a friend/artist they did their M.F.A. with; they saw a bench outside with a space reserved for a plaque but no plaque – so they made one.

VPB: When it comes to having your work exhibited, how do you feel about others (curators, gallery owners, etc.) making decisions about how to display your work? Do you give clear instructions or are you open to letting someone else make those decisions?

LFY: I love to see curators as collaborators; also I see my work too much, so I can’t see it in a fresh way. I sometimes give instructions, often I give options but really the people who work in, or curate in, a specific space have a better sense of how things could be displayed within their space. I value the new perspectives I get from seeing my work exhibited in different ways and how the layouts allow the viewers to find the hidden meanings in my art that I sometimes get to come to discover and reflect on as well.

Victoria and Sabrina would like to extend special thanks to Gwen Baddeley for editing and encouragement.