Politicizing Poutine

Ian Alexander Cuthbertson

Humanities Faculty

This blog post originally appeared on Culture on the Edge

Poutine, a delicious mess of french fries, cheese curds, and gravy, has recently been described as Canada’s national dish. Given poutine’s origins in rural Québec, these claims shed light on the tensions at play in the ongoing construction of Canadian identity.

Poutine’s status as Canada’s national delicacy remains unofficial despite a recent campaign to give poutine the national recognition it deserves.

Yet marketing campaigns aside, poutine is already widely recognized as being quintessentially Canadian.

Locating (or rather fabricating) a shared national culture is important in Canada, which recently celebrated its sesquicentennial. Canada’s pre-Confederation colonial history in which French settlers, who eventually claimed a unique identity as Canadiens, were later colonized by English settlers in successive waves after 1763 has resulted in a country long divided along linguistic and cultural lines: a country consisting of two solitudes.

These linguistic and cultural differences have long fueled nationalist and sovereignist movements in Québec and in 1980 and 1995 Québec held referenda to separate from Canada and become a sovereign nation. Although federalists narrowly defeated the separatists, the Canadian government officially recognized Québec’s distinct cultural identity in 2006 when parliament passed a motion asserting, “the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada.”

But it would be a mistake to view Canada as a country divided neatly in two. The plight of indigenous or First Nations peoples in Canada continues despite recent commitments to renew a ‘nation-to-nation’ relationship, leading some to refer to indigenous communities as Canada’s third solitude. Moreover, Québec is not the only province to consider independence from Canada.

Canada has long struggled to assert its own unique national identity and to find shared cultural markers. In 1971 Canada introduced an official policy of multiculturalism, which has led some critics to claim that Canada has no distinct culture of its own. In an interview with the New York Times r, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau remarked that Canada has “no core identity” which has led some to wonder whether Canada may be the world’s first post-national country and others to assert that Canada does indeed have a culture of its own, no matter what the Prime Minister thinks. Faced with such an identity crisis, is it any wonder that Canadians are eager to identify shared cultural values, practices, and meals?

The problem is that poutine, like many other notable markers of ‘Canadian’ identity (ice hockey, toques, the Canadian national anthem) originated in Québec. The dish was invented either by Fernand Lachance in Warwick in 1957 or else in Drummondville by Jean-Paul Roy in 1964 and although its precise origins are obscure, Québec’s claim to having invented Canada’s purported national dish is undisputed. Even in its brief appearance on the American television program Modern Family, the dish is described as a “French-Canadian delicacy.”

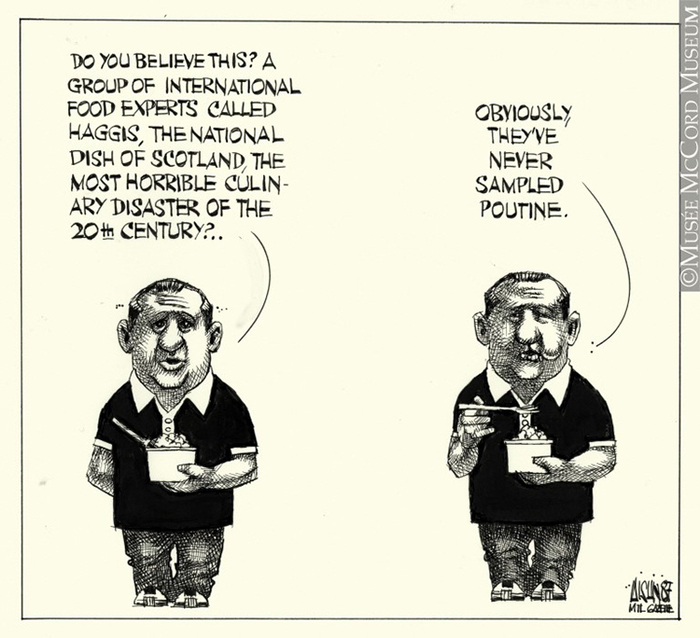

The dish that has been touted as quintessentially Canadian was practically unknown outside of Québec until the mid 1980s. The first brief mention of poutine in The Globe and Mail, then Canada’s largest daily newspaper, occurs in 1982 where it is described as a “plate of mystery.” Two years later, poutine is described as an “unlikely combination” of cheese curds, french fries and gravy that makes for an “odd dish.” Poutine has not always enjoyed its current lauded status, as a cartoon drawn in 1987 by the Montreal Gazette’s political cartoonist Aislin suggests.

So is poutine Canadian or Québécois? As is the case when considering any strategic act of identification, this question misses the point entirely. For those interested in constructing a shared Canadian identity in the face of multiculturalism and in the wake of its colonial history (as well as for those hoping to sell oddly flavoured lip balm), poutine is “uniquely Canadian.” For Montréal chefs like Chuck Hughes, poutine has instead been appropriated by the rest of Canada and remains quintessentially Québecois. In other words, poutine’s status as either Canadian or Québécois is political. Its contested status is the result of a variety of stakeholders laying claim to a fabricated essence to serve their own particular interests.

La Banquise, a well-known poutinerie in Montréal, provides a history of the (in)famous dish in both French and English on its website. Both versions describe poutine as ‘our national dish.’ But whereas a Québécois reading the description in French will likely interpret the word ‘nationale’ to refer to Québec, Canadians reading it in English will likely interpret ‘national’ to refer instead to Canada. In this case the restaurant is presumably interested in selling poutine, which perhaps explains its willingness to let both Canadians and Québecois have their poutine and eat it too.